Elizabeth church resurrects stories of African American ancestors on burial grounds

They met by chance at a cemetery behind a church in Elizabeth. One, a Black woman, was the church pastor seeking to preserve the legacy of enslaved ancestors. The other, a white woman, was searching for an ancestor who was part of the Continental Congress.

Pastor Wanda Lundy later invited Nancy Benz to join the nonprofit 313+ Ancestors Speak project, which honors enslaved and free African American people buried at Old First Cemetery at Siloam-Hope First Presbyterian Church on Broad Street near Caldwell Place.

Now, the women work hand in hand to fulfill the nonprofit’s goal of building a 21-foot monument in the cemetery to the African ancestors and telling their stories, conducting research and creating a dedicated interactive museum.

“I would like to see the descendants of the African people buried in the cemetery and the descendants of the European people talking about whether… we agree that everyone should have access to the rights outlined in the Declaration of Independence,” said Lundy, 63, of her broader hopes for the project. “And if we don’t, how we can get there?”

“If we don’t have those conversations, we have wasted our time in a lot of ways,” she added

Research specialist James Amemasor works at New Jersey Historical Society and says this project is critical.

“It acknowledges the presence and contributions of African people to the growth and development of Elizabeth and New Jersey,” he said, “Doing so is critical to make the history of the city and the state inclusive and complete.”

A search for ancestors

Benz and her husband were searching for the grave of Benz’s sixth great grandfather, Stephen Crane, on a Sunday afternoon in 2021 when she met Lundy, who always introduces herself to people she sees in the cemetery. Together they spent the entire afternoon looking for Crane’s gravesite.

About a month ago Lundy called Benz from the cemetery and “immediately handed the phone to a very distant cousin of mine who lives in Arkansas,” said Benz, 70, of Cranford.

Benz’s cousin was on her way back from Maine and had stopped at the cemetery to visit the graves of her relatives, “the Magies,” as in Magie Avenue in Elizabeth and Union. The Magie family, originally spelled McGhie, Benz said, helped found Elizabethtown, now Elizabeth, and the First Presbyterian Church of New Jersey.

Old First’s PAINFUL PAST

Amemasor, New Jersey Historical Society’s research specialist, said Elizabeth was the first English settlement in New Jersey and African people were brought here.

The state’s founders formed First Presbyterian Church, which only welcomed English settlers. Siloam Presbyterian Church was created for enslaved and free African Americans.

A third church, Hope Memorial Presbyterian, was later added. In 1985 Siloam merged with Hope Memorial. By 2019, Siloam-Hope merged with First Presbyterian to become Siloam-Hope First Presbyterian Church.

Old First was the only cemetery in New Jersey until the 17th century. New Jersey’s founders, other Europeans, and African Americans, about 2,000 total, are buried there.

Black people were not allowed to be buried alongside whites in the segregated cemetery, said Elizabeth native Leonard Jackson, 71, recounting the stories his late mother told him. So, he said white people were buried in the front, and Black people were buried or dumped in the back – mostly in unmarked graves, he said.

Some 117 African Americans have first and last names, another 40 have either a first or last name, and the remainder are unknown. So far, there is only one African American ancestor listed as free. Her name was Hannah. She was 66 when she died on March 11, 1821, and her cause of death was unknown.

Lafayette Boyleston is one of the few whose grave has a tombstone.

“We know he is one of the ancestors because, in the top right corner of the tombstone, it has the letters Col’d, which stands for colored,” Lundy said. “We know that Lafeyette Boyleston’s slave owner paid for his funeral. That is some of the research that I found,” she said.

Before she became pastor in 2019, someone had already researched the church’s “Records of Burial Book” of everyone interred in the cemetery and created two lists — one of Europeans and the other of Africans. When Lundy saw that there were 313 names of Africans on the list, she created the 313+ Ancestors Speaks project.

“To have people buried in unmarked graves, and then amongst them, there was also continental soldiers, my motivation was to correct the social wrong,” he said. “They shouldn’t be forgotten and especially their service to this country.”h of Elizabeth, New Jersey,,” with instructions to hold onto it.

“They didn’t even put their names on the stone,” said Jackson, a 313+ Ancestors Speak board trustee. “All you will see is colored, and they are not in good shape at all.”

RIGHTING A ‘SOCIAL WRONG’

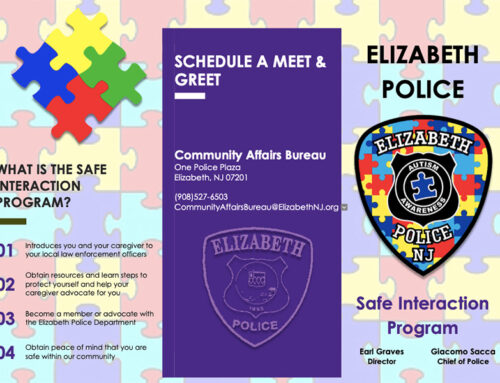

The board of trustees for 313+ Ancestors Speak Project consist of 16 people, a mix of congregation members, police officers, community members and historians.

Elizabeth police chief Giacomo Sacca said he got involved in the project to help right a “social wrong.”

“To have people buried in unmarked graves, and then amongst them, there was also continental soldiers, my motivation was to correct the social wrong,” he said. “They shouldn’t be forgotten, and especially their service to this country.”

The hope of building the monument also sends a message to the community that we can work together to pave the way for the future,” he said.

Linda Caldwell Epps, 70, an Elizabeth native, was interested in history and began doing research as a volunteer.

“We no longer can say we have done well historically if we are not inclusive of other cultures and races, and it highlights that they made contributions to life as we know it today, the food we eat, the customs,” she said. “It’s not just something that’s constructed exclusively by Europeans.”

Lundy, thinks back to the day she met Benz at the cemetery. She said she gets chills, thinking about how she has been connected to many different people almost in a kismet way.

“Identity is important,” she said, “and I think that the better connected, especially we as human beings are to our identity, the better we will be able to get along with other people.”

This article originally was posted here