The ancestors are calling: Finally, acknowledging Blacks forgotten in historic church cemetery

When he was a boy, Leonard Jackson caught the school bus every day next to the old cemetery at First Presbyterian Church in Elizabeth, New Jersey. He never knew the cemetery’s secret.

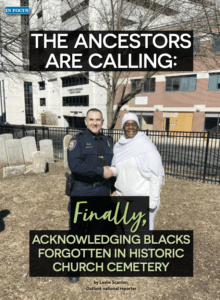

As a young patrolman, Giacoma Sacca, now the chief of police in Elizabeth, walked

a beat that included the First Presbyterian Church property. Sometimes “I’d walk in and explore,” wandering through the rows of headstones – an estimated 2,000 or so of them, dating from 1701 or even earlier.

Sacca didn’t know either, until Wanda Lundy, now the pastor of the church, took him into the cemetery in February 2020, pointed to one section and said, “You know, we have 313 buried slaves here,” in unmarked graves.

That discovery has led to the creation of the 313 Project — an effort led by Lundy to identify as many of those persons as possible, enslaved and free, to know their names and their stories and to erect a monument in their honor. The number 313 is fluid — there likely are more, as the records are incomplete, although the existence of the graves and the likelihood that many were enslaved is all but certain.

According to records kept by the church sexton, there’s a man who died in January 1798, the “Negro man of John Mulford.”

There’s “Hannah, a free black,” who died in 1821 at age 66.

And Pompey, who died in March 1797, listed in a property inventory of the Woodruff family.

There’s a child, a year and a half old, no name, no cause of death, no parents listed, just that the child was “col’d,” for “colored,” and died in 1849 — beloved certainly, but that’s all that’s known.

“It is the story of African people in

this country, that we have been so disconnected from our history, in so many different ways,” Lundy said. “As an African American, as a Black person in this country, you live with it every day. They are in unmarked graves — they are not marked. But the European graves are marked.” For those who were enslaved, “they weren’t citizens, they weren’t even considered human. They weren’t even considered 3/5 of a human being then. What was life like for them? We want to know.”

Even many with deep roots in Elizabeth never knew about the unmarked graves.

“I’ve been a police officer in Elizabeth for over 25 years,” Sacca said. “The cemetery is right in the middle of our town. The church is a very historic landmark. It’s been there since the founding of Elizabeth, was the very first building in Elizabeth.” Yet with all that history he never heard anyone speak of enslaved people being buried in the cemetery.

His response to what Lundy told him: “It’s something people need to know.” A key Revolutionary War battle was fought on this property in 1780, Sacca said — and it’s likely enslaved Blacks were either part of or assisted the patriot forces.

“Just because somebody did something 200 years ago doesn’t mean we have to accept it now,” he said. “They need markers so that people aren’t just walking over their graves as if they are nothing.”

“Just because somebody did something 200 years ago doesn’t mean we have to accept it now,” he said. “They need markers so that people aren’t just walking over their graves as if they are nothing.”

For Jackson, who is Black, it’s more personal. He believes he has family members buried there. “I don’t think they were decent burials. They were just dumped in there, probably in a cardboard box,” their names and histories not recorded. “These people never had a voice. And we want to give them a voice.”

The ancestors’ voices

She can hear the ancestors calling.

The first time Wanda Lundy visited Siloam Hope First Presbyterian Church in Elizabeth, New Jersey, in the summer of 2019, she had the strongest sense: Don’t park close by the building. She listened to that inner voice, intuitively choosing to park at the far edge of the lot.

A few months later, she came back — invited to help with a commemorative event called “Four Centuries in a Weekend,” which traces the history of the community back to the earliest days of the colonies and the Revolutionary War. That history was full of references to whites whose names dot the history books — including Alexander Hamilton and Aaron Burr, who attended Snyder Academy in the 1700s on the grounds of the old First Presbyterian Church, and James Caldwell, who served as pastor of First Presbyterian and was known as “The Fighting Parson” for his bravery in fighting the British.

What got her attention, though, was the lack of reference to any Blacks in that history — until she heard a woman say, matter-of-factly, “Oh yeah, we have 300 slaves buried in the cemetery.”

Lundy believes it was the voices of what she calls “the ancestors” that she first heard when she drove up to the church, where she felt that strong, insistent urge to keep to the side — she’s now convinced there are likely more graves underneath the parking lot.

She believes the ancestors brought her to Elizabeth, where in late 2019, she was called as the pastor of Siloam Hope First Presbyterian Church — a merged congregation that includes First Presbyterian Church, what was once the congregation where slaveholders worshipped; Siloam Presbyterian Church, a new congregation the white Presbyterians established a few blocks away from First Church for the enslaved Blacks; and Hope Presbyterian Church, another small congregation.

“We really can’t move forward until we allow the healing to take place,” Lundy said. “For people of color, much of our history has been hidden, has been distorted, we’ve been told we didn’t even have a history. Now is the time for us to dispel that mistruth, that lie. The beginning of finding that story is with our ancestors.”

But this is not just the story of one historic cemetery at one New Jersey church. Another hidden truth: It’s not unusual for Black and Indigenous graves to go unmarked and unnoticed, to be part of the geography of many communities around the country.

The reality that Black Americans – some of them babies, some likely war veterans – are buried in unmarked graves in a church cemetery “is completely routine, all over the country and especially in the Northeast,” said David Staniunas, a records archivist with the Presbyterian Historical Society.

It’s estimated, for example, that in Bethel Burial Ground – a 19th-century cemetery in Philadelphia that’s underneath the surface of what’s now Weccacoe Playground on Queen Street, and which lies about a half-mile from Mother Bethel A.M.E. Church – maybe 5,000 people are buried, about half of whose names are known.

In Lower Manhattan in New York City, a federal construction project in 1991 uncovered the remains of 419 Blacks buried there from the middle 1630s to 1795 — now commemorated by the African Burial Ground monument.

In downtown Portsmouth, New Hampshire, the African Burying Ground Memorial Park marks an area that in the 1700s was used for burying Blacks who had died, and that later was forgotten and paved over.

Linda Caldwell Epps, a public historian with 1804 Consultants, said that growing up in Elizabeth, said she had no idea, “none whatsoever,” that Blacks were buried in unmarked graves at the First Presbyterian Church cemetery. But “it’s very common,” Epps said, “not only to have them in unmarked graves in majority-white cemeteries,” but to have whole burial grounds that are unmarked. … The sacred burial grounds are becoming more and more endangered as we expand in population and in our building needs and wants.”

Such stories are local, but with broader meaning as well. All over the country, Presbyterian congregations committed to anti-racism work are beginning to investigate their own stories, digging into their relationship to the land and to wealth and to their own community’s history with systemic racism.

A $10 million restoration project begun in the late 1990s included work on First Presbyterian Church, the parish house and the cemetery, “completely done, top to bottom,” said Robert Higgs, who served as the congregation’s pastor at the time. About 1,100 headstones were restored, with work done by a historic preservation firm from Philadelphia. What wasn’t part of that project, in part because the money ran out, Higgs said, was any attempt to publicly honor the unnamed Black Americans buried over 200 years in this historic site.

Calling the names

Every Sunday afternoon, Lundy leads a Zoom call to do research on the 313 Project. On one recent call, James Amemasor of the New Jersey Historical Society traced the history of slavery itself in New Jersey, going back to before the nation’s founding. The Historical Society has the log of a slave ship that in 1732 brought 200 enslaved Africans to Port Amboy.

“It’s a document that’s older than the country,” Amemasor said. “The American story is the story of freedom,” and “the African American story is central to that story. … How did Africans survive in a very strange land? What did they do? What were their contributions?”

“It’s a document that’s older than the country,” Amemasor said. “The American story is the story of freedom,” and “the African American story is central to that story. … How did Africans survive in a very strange land? What did they do? What were their contributions?”

Colonial records often refer to “my Negro boy, my Negro girl, mulatto or wench. … They were never given a name. They’re our unknown ancestors. But they are there.”

While an enslaved person’s name may not be known, “the contributions they made to the daily life of the community is indescribable,” Lundy said. “This country would not be standing without the blood, sweat and tears of our ancestors.”

Virginia Huff, a member of Siloam Hope First, said many Blacks feel disconnected from their own families’ stories because of that anonymity. “It is the hardest thing to find my family because there are no names,” she said. “Only through DNA have I been able to connect with some people, but we don’t know how we are related. We don’t even tell our own stories. … People come here from all over, places of oppression, to be free. The people who were born here, were raised here, haven’t had the same right to be free.”

For the cemetery in Elizabeth, some of the names of those buried in unmarked graves are known. Some records kept by sextons for First Presbyterian have survived — including a book one sexton apparently took home by chance the night a fire burned down the church and destroyed earlier records.

Jackson said his mother, Margaret, gave him a typewritten list of 316 names before she died in 2014, although he’s not sure where she got the list.

Epps did some research as well, for the restoration project that Higgs led. She found, for example, that in one month an extraordinary number of children passed away, probably from illness.

“I really feel this is my duty and my honor, whatever I can do to give homage to their lives and honor to what they did,” Epps said. “They helped to build the city as they did the country. I am a reparations person. I don’t know exactly what shape or form” that should take, she said, but she believes something needs to be done.

Police chief Giacoma Sacca speaking in the cemetery at the First Presbyterian Church in Elizabeth, New Jersey.

Sacca, the police chief, is trying to build financial support for the 313 Project and the possibility of a monument. The police union has donated about $3,500 from its annual fundraiser. Sacca helped to start an online fundraising project, where donors can purchase engraved bricks to raise funds for the monument, and is applying for grants.

At least one marked grave in the First Presbyterian Church cemetery is known to be a Black man: LaFayette Boylston, who died in 1849 at age 24 years. In the top right corner of his gravestone is the inscription “Col’d” – for colored. Possible cause of death: consumption.

“The fact that African people survived in this country is telling of the strength and the resiliency of the people,” Lundy said. “That’s the story that we want to tell of our ancestors. At least 40% of those that are buried there were less than 20 years old — they were young,” she said. Lundy stops, and sighs.

On All Saints Day in 2020, Siloam Hope First Presbyterian Church read aloud the names, one by one, of the 117 Blacks buried in the cemetery who have so far been identified. “We will do it again every year,” Lundy said. “My hope is that this year we will have more names to call. … They want their names to be called.”

This post was originally posted here